In the autumn of 1934, days before the publication of Burmese Days in New York, George Orwell penned the introduction to the French translation of Down & Out in Paris & London, the book that launched his literary career. His introductory text was slotted in between Panaït Istrati’s preface and chapter one of La Vache enragée.

By the time Orwell left Paris at the end of 1929, his French was of a good standard, as shown in the excellent Correspondance avec son traducteur (J.M.Place 2006). But the constructions used and the fluidity of the language in his French introduction do not match the letters he exchanged with his French translator. The text was most probably written in English and then translated by either R.N.Raimbault or Gwen Gilbert who worked on the book. The English original, much like the original manuscript of Down and out in Paris and London, has never come to light.

Orwell’s introduction, reproduced below, is therefore reverse-engineered; I have translated it – with Orwell’s voice in mind – back into something I hope approaches its original form.

Duncan Roberts – April 2024

* Translator’s note: Hôtel garni was a term common in France and Germany and described a hotel that provided mid-term, non-tourist, accommodation. It was a popular choice for workers. There were more than 20,000 such hotels that housed 11% of Parisians in the interwar period.

George Orwell’s Introduction to La vache enragée

My dedicated translators have asked me to write a short preface for the French edition of this book. It being likely that any French reader will wonder as to the circumstances that led me to be in Paris during the period I describe, I feel that it would be best to start with some biographical details. I was born in 1903. In 1922 I went to Burma where I joined the Imperial Police force. The job could hardly have suited me less. In 1928, whilst on leave in England, I resigned with the hope of making a living as a writer. I succeeded about as well as any young person who embraces the literary way of life — that is to say, not at all. My first year’s earnings as a writer barely brought in 20 pounds.

In the Spring of 1928, I left for Paris, to live cheaply and to give myself time to write two novels – which, I’m sorry to say, were never published – and also, to learn French. One of my Parisian friends found me a room in an Hôtel garni*, located in a working class area that I’ve briefly described in the first chapter of this book and that I’m sure any self-respecting Parisian will have no trouble recognising. During the summer of 1929, I’d written two novels that publishers turned down and I found myself quite broke and in urgent need of work.

At this time, it wasn’t against the law – not strictly at least – for foreigners in France to hold down a job, and I felt it made more sense to stay where I was rather than return to England where there were roughly two and a half million unemployed. So I stayed in Paris and the events I recount took place at the end of the Autumn of 1929.

As to the truthfulness of my tale, I can confidently claim that I have not exaggerated, except in the way that all writers exaggerate, that is to say by selecting. Though I felt no obligation to recount events in the order in which they occurred, all those related did occur at one time or another. I did however steer clear, whoever possible, from writing accurate portraits. All the characters I have described in the two parts of this book are purely representative of the Paris or London classes to which they belong and not of actual individuals.

I should really point out that this book in no way aspires to give a broad view of life in Paris or London, but merely to depict one particular aspect. As almost all the situations and events I found myself mixed up in share something of a repugnant nature, it is highly probable that I give the impression of someone who believes Paris and london to be abominable places. This was never my intention, and if at first glance this is how it appears, it is only because the subject of my book, namely poverty, is essentially devoid of charm. When your pockets are empty, you are likely to view any town or country in a less than favourable light, and people become either companions in suffering or enemies. I felt it particularly important to point that out for my Parisian readers; I would be mortified if they believed I held the least bit of animosity towards a city of which I have such fond memories.

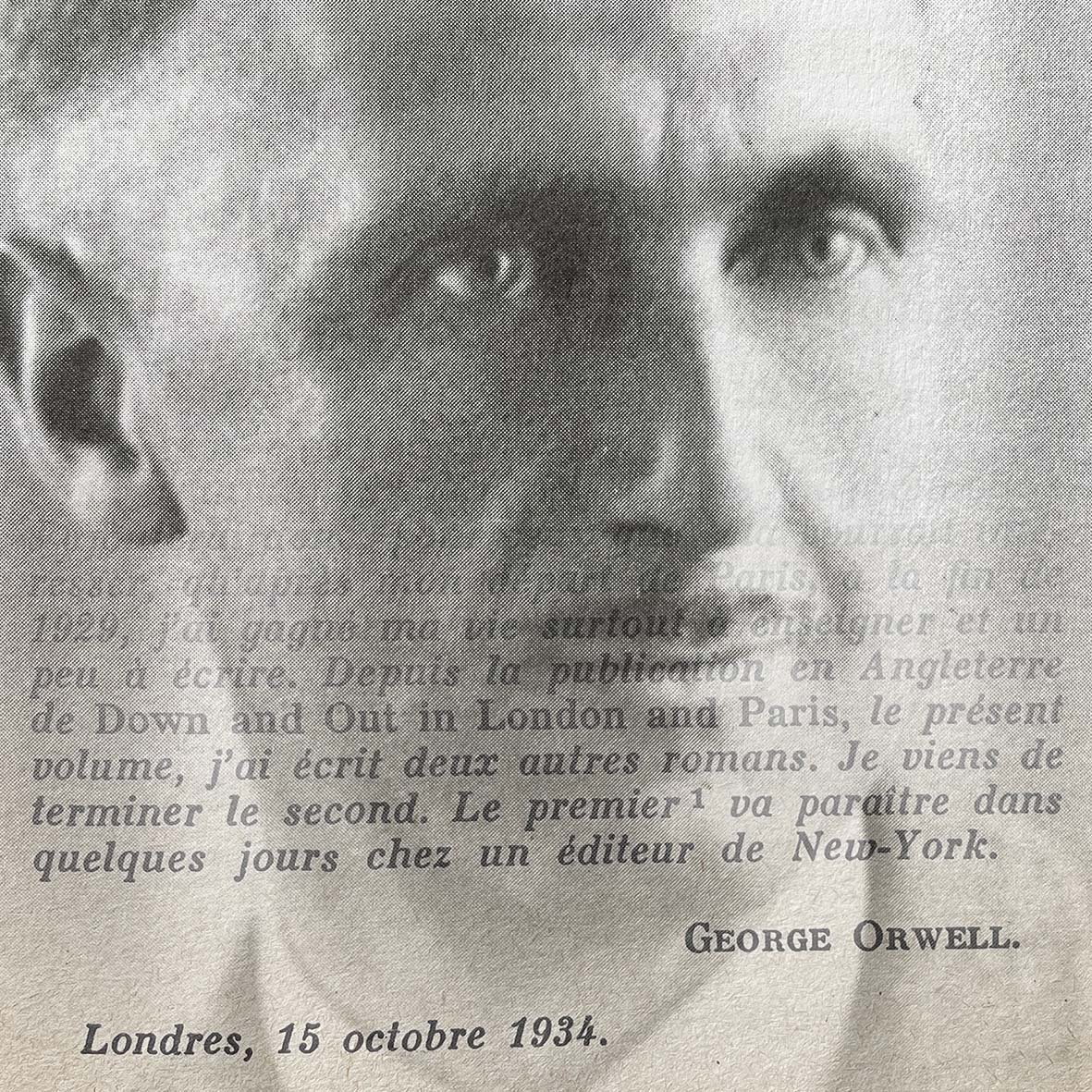

At the beginning of this preface I promised I would offer my readers some biographical details. For those who may find it of interest, I will therefore add that after leaving Paris at the end of 1929, I earned a living primarily by teaching and a little by writing. Following the publication in England of this book, Down & Out in Paris & London, I have written two further novels, the second of which I have just completed. The first (Burmese Days) will be published in New York in a few days time.

George Orwell

London, 15th of october 1934

Share this:

Tags: 1928, 1929, 1934, down and out, Eric Blair, Gallimard, introduction, la vache enragee, orwell, paris, pot de fer, Raimbault