Panaït Istrati (1884-1935), the writer of the French preface to Orwell’s “Down & Out in Paris & London” (La Vache Enragée) died a pariah, reviled and slandered by the Communists for daring to speak ill of Stalinist Russia in 1929. Orwell died in 1950, also of tuberculosis, and at the same age as Istrati, but it would appear that the two writers had far more in common…

Panaït Istrati was born in 1884 in Brăila, a south-eastern port “on the Danube where all the strains of the Balkan countries and the bare-footers from the Near-East mingle.” Mihail Sebastian (1907-1945), another great Romanian writer, had a perfect command of French but published all his works in Romanian, and Ionesco, especially in his youth, wrote in both languages. Istrati, a gifted polyglot who also spoke Turkish and Greek, belonged to that family of writers who, like Samuel Beckett and Milan Kundera, chose to write in French.

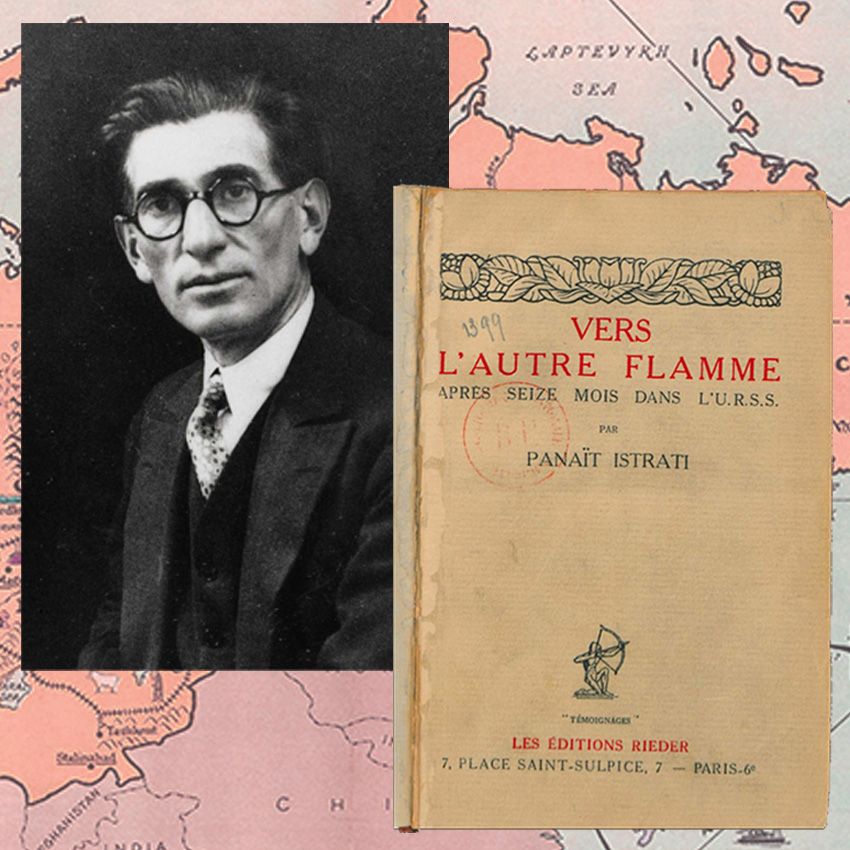

When Istrati was asked to preface Orwell’s first book, he had held down multiple jobs: house painter, pig farmer, photographer, the list goes on… and already had a fine collection of novels published by Rieder; 18 books in 12 years! But since publishing Volume One of the trilogy Towards the Other Flame (October 1929), his star had dimmed considerably and he was now a broken and isolated man. The self-taught proletarian who had come to socialism “to spread goodness” was the victim of a multi-pronged attack, both in France and in Romania where he had returned to live out his final years. He had even managed to alienate his idol, mentor, and protector, Romain Rolland.

Barbusse, Istrati, Orwell

Was Orwell aware of all this in 1935 when he first read the preface to his book? Probably not, judging by the correspondence with his translator René-Noël Raimbault. Did Orwell know that Henri Barbusse, the man who had published his first articles in Monde, and who he may have met in Paris in the late 20s, had since then been waging an abject campaign against the Romanian writer? Istrati, who had also contributed articles to Monde, was refused the right to reply within the pages of Barbusse’s review.

In October 1927, Panaït Istrati, a committed communist, set out for the USSR to mark the 10th anniversary of the Revolution.

“But I was firmly convinced that from the moral point of view, from the point of view of elementary justice, the dictatorship of the proletariat was fully justified…could only be healthy.”

After Moscow, he visited Leningrad, where he met Victor Serge, then headed for Ukraine and the Caucasus before returning to Moscow with Níkos Kazantzákis. The Greek and the Romanian were determined to spread the Bolshevik message at the next stop on their voyage: Greece, or that at least is what they wrote in a joint letter to Stalin. Once in Greece however they were charged with communist agitation. Istrati then returned to the USSR, this time to Kiev, where Kazantzákis soon joined him. The trip continued on to Murmansk, Bekovo, Moscow where they met Maxim Gorky, and Nizhny Novgorod, where Istrati met Henri Barbusse. The trip ended in December, in Leningrad, in the company of Victor Serge. On the 15th of February 1929, Istrati returned to Paris. On the 20th of May, he completed Volume One of the trilogy Towards the Other Flame (published in October of the same year) and wrote to Romain Rolland.

“My friend, I’ve thrown everything out the window.”

It would take too long to recount in detail Panaït Istrati’s shift from communism to anti-Stalinism, but Towards the Other Flame was a firebomb, a veritable diatribe against the Soviet regime and was all the more powerful for having come, for the first time, from the pen of a left-wing writer; a full seven years before Gide’s Retour de l’URSS and Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Mea Culpa.

The eternal opponent

The case he puts forward is devoid of ambiguity…

“There is no longer any question of socialism, but of a terror that treats human life as raw material for social warfare, and which is used for the triumph of a new and monstrous caste that loves Fordism […] This caste; ignorant, vulgar, perverse, is mostly made up of young people who have come into the world since the beginning of this century.”

In summary, after listing the means of power, Istrati sums up the essence of the new caste.

“…all empty rhetoric, which it uses to lord over and dominate.”

Romain Rolland tried to dissuade him from publishing his essay, but Panait Istrati, in keeping with his ethics and his quest for truth and freedom, ignored his friend’s exhortations and became “the man who subscribes to nothing….the eternal opponent.”

“…in the skin of a fascist”

The other two volumes of Towards the Other Flame (Soviets 1929 and La Russie nue) credited to Istrati but written by Victor Serge and Boris Souvarine respectively, were published shortly afterwards. Almost immediately, Barbusse began discrediting and slandering Istrati in the columns of Monde. L’Humanité followed suit, and many French Communists, such as Paul Nizan in Commune, towed the party line. Most reprehensible of all was the anti-Semitic trial brought against Istrati, where the vagabond writer was accused by Barbusse of being a member of the Stelescu group, a branch of the Iron Guard, the Romanian fascist organisation.

Panaït Istrati’s funeral, April 1935. The fascist, Mihai Stelescu follows the writer’s coffin, an attempt by the Romanian Iron Guard to appropriate his name and work.

These falsehoods would even tarnish Istrati’s name beyond the grave. A prime example being his obituary, published with palpable glee, in L’Humanité on the 17th of April 1935.

“Yesterday we learned of the death of Panaït Istrati. This former revolutionary writer died in Romania in the skin of a fascist”

A few days earlier, on the 31st of March, Bernard Lecache, head of the International League against Antisemitism, had written in Le Bulletin de la LICA.

“…but Panaït Istrati has become an anti-Semite. He spits in the dish from which he ate. He scorns and insults his former saviours. He no longer wishes to enter their synagogue except to desecrate it.”

Towards redemption

This propaganda proved to be particularly destructive and effective, reaching all the way down to the grassroots level: Duncan Roberts, the author of this blog and the book Orwell in Paris, tells the story of his French grandparents, staunch communists, getting rid of their books by Istrati and railing against other turn-coats such as Yves Montand and Simone Signoret. It was not until 1968, with the creation in France of the Les Amis de Panait Istrati, and the republication of his works by Roger Grenier at Gallimard, in four volumes, that his redemption truly began. All the allegations made by Barbusse and the Communists were dismantled one by one. In 1984, David Seidmann re-established Panaït Istrati’s philosemitic truth with the publication of L’Existence juive dans l’œuvre de Panaït Istrati – The Jewish question in the works of Panait Istrati.

Panaït Istrati, an uncompromising left-wing writer and a lover of truth, was the object of an antagonistic propaganda battle, that in a way foreshadowed the Communist censorship of Orwell’s books and the attempts by right-wing reactionaries to appropriate his work.

Nicolas Ragonneau

Translated by Duncan Roberts

Nicolas Ragonneau’s books and blog on all things Proust can be found here: www.proustonomics.com

Sources:

Notes et reportages d’un vagabond du monde, a series by Panaït Istrati published in Monde from 16 June to 21 July 1928.

https://imec-archives.com/archives/fonds/103IST

https://www.panait-istrati.com

Share this:

Tags: 1928, 1929, André Malraux, communism, down and out, Eric Blair, Henri Barbusse, Istrati, orwell, paris, Romania, Stalin